Silent films, old and new

Sunday | April 21, 2013 open printable version

open printable version

Blancanieves

Kristin here:

February and March have been good to silent cinema. Time for a round-up of some highlights as we impatiently anticipate Il Cinema Ritrovato, coming up in a little over two months.

Publications on Albert Capellani

In reporting on the 2010 and 2011 programs of Il Cinema Ritrovato, I highlighted one of the festival’s major revelations, that of the silent films of Albert Capellani. These generous doses of Capellani’s splendid films were put together by Mariann Lewinsky, who realized his importance after she included some of his shorts in her annual “Cento Anni Fa” programs. In my entries I argued that Capellani was revealed as one of the early cinema’s great masters. (The 2010 entry is here, and the 2011 one here.)

Not surprisingly, during the intervening years, scholars have been busy researching Capellani’s films and career. March 6 to 24 saw a major retrospective at the Cinémathèque Française. (Information on the program is still available online, as is a detailed press release.) Shortly before it began, the first biography appeared: Christine Leteux’s Albert Capellani: Cineaste du Romanesque, with a foreword by Kevin Brownlow.

Leteux discovered Capellani in May of 2012, thanks to seeing Notre-Dame de Paris and Les Misérables at the Forum des Images in Paris. Setting out to learn more about the filmmaker, she realized how thoroughly his memory had nearly vanished from film history. She sought out and received the cooperation of his grandson, Bernard Basset-Capellani, whom she describes as “intarissable” (inexhaustible) on the subject.

The result is a solid, traditional biography, with chapters mostly organized around the companies for which Capellani worked (Pathe, SCAGL, World, Mutual, and so on) and some of his key films (Les Misérables, The Red Lantern). The prose style is easily readable French, at least to someone like me with an average knowledge of the language. For an interview with Leteux concerning the book, see here.

The book is on sale at the Cinémathèque’s shop, which unfortunately does not sell online. It was supposed to be available on Amazon.fr, but so far is not. The easiest way for those outside France to order it is through three third-party book-sellers on amazon.fr, all offering it at the cover price of 14.90 €. Leteux’s book is a vital source for anyone interested in early cinema.

I was pleased to see that the last chapter ends with some quotations from my second entry on Capellani, ending with “With the end of the main retrospective, however, it is safe to say that from now on anyone who claims to know early film history will need to be familiar with Capellani’s work.”

The book includes a filmography and list of films available on DVD. These include a new one, a restoration of The Red Lantern by our friends at the Cinematek in Brussels, available on Amazon.fr or directly from the Cinematek’s shop.

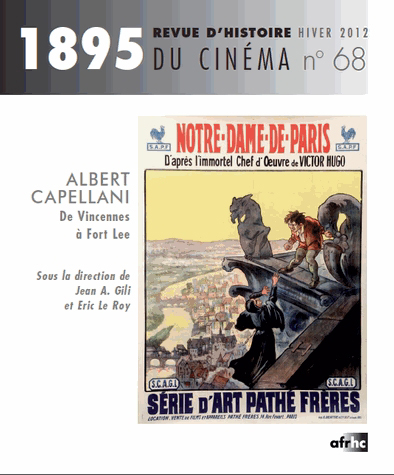

The French-language historical journal on cinema, 1895, timed its March, 2013 issue to coincide with the Cinémathèque’s retrospective. It is entirely devoted to Capellani. I have not had a chance to see it yet, but the table of contents is available here. The only online purchasing source for individual issues I have found is here; the page gives a lengthy summary of the contents.

Mariann continues to search for more surviving prints for restoration and eventual inclusion in future editions of Il Cinema Ritrovato. She has sent me some tantalizing news about recent discoveries and restorations. There will be a third Capellani season in 2014. This will probably include some of the director’s American films: Social Hypocrites (now restored), Flash of the Emerald (the one surviving reel), Inside of the Cup (surviving but so far with no projection print), Eye for Eye (two surviving reals), Sisters, and the French film Le Nabab. Other possible restorations include House of Mirth, La belle limonadiere, and Oh Boy!

A description of the 2013 Ritrovato festival is available here.

Nanook and friends

Early this year we posted our annual list of the ten best films of ninety years ago. It featured the classic early documentary, Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North. In March our friends at Flicker Alley released a two-disc Blu-ray edition of Nanook paired with the 1934 Danish feature, The Wedding of Palo (Palos Brudefærd). The latter is one of those titles that one occasionally encounters on the fringes of older historical surveys, but it has been difficult indeed to see. This new print is a 2012 restoration from a George Eastman House original 35mm nitrate copy.

Nanook is familiar enough, but The Wedding of Palo is not. It was made by the Danish explorer and anthropologist Knud Rasmussen, who appears in a brief introductory passage. Clearly he was influenced by Flaherty’s work. He combines a simple fictional narrative with documentary scenes of traditional Inuit life in eastern Greenland. The basic story involves the heroine Navarona, whose brothers are reluctant to lose their housekeeper by allowing her to marry. Two men of the tribe court her and come into violent jealous conflict. Interjected are sequences of a salmon hunt, a festival, a traditional song duel between the two rivals, and a polar-bear hunt. The staged dialogue scenes involve sound recording, with no subtitles but the occasional brief intertitle to translate.

Nanook is familiar enough, but The Wedding of Palo is not. It was made by the Danish explorer and anthropologist Knud Rasmussen, who appears in a brief introductory passage. Clearly he was influenced by Flaherty’s work. He combines a simple fictional narrative with documentary scenes of traditional Inuit life in eastern Greenland. The basic story involves the heroine Navarona, whose brothers are reluctant to lose their housekeeper by allowing her to marry. Two men of the tribe court her and come into violent jealous conflict. Interjected are sequences of a salmon hunt, a festival, a traditional song duel between the two rivals, and a polar-bear hunt. The staged dialogue scenes involve sound recording, with no subtitles but the occasional brief intertitle to translate.

As in Nanook, the non-professional actors are remarkably natural, especially the “actress” portraying the heroine. There is a cute young boy brought in at intervals for comic appeal, and the members of the village seem always to be laughing and enjoying a suspiciously carefree life. The film has the advantage of more spectacular scenery than that in Flaherty’s film, with huge mountains and glaciers in place of the vast ice-covered vistas (see bottom image).

As usual, the Flicker Alley team has gone beyond the call of duty with this release. It includes not only the two features, but six bonus films, as described in the press release:

Nanook Revisited (Saumialuk) by Claude Massot was made in the same locations used by Flaherty. It shows how Inuit life changed in the intervening decades, how Flaherty consciously depicted a culture which was then already vanishing, and how Nanook is used today to teach the Inuit their heritage. Nanook Revisited was produced in 1988 on standard definition video for French television. Dwellings of the Far North (1928) is the igloo-building sequence of Nanook re-edited and re-titled as an educational film; Arctic Hunt (1913) and extended excerpts from Primitive Love (1927) are by Arctic explorer Frank E. Kleinschmidt; Eskimo Hunters of Northwest Alaska (1949) by Louis deRochemont shows many activities seen in Nanook thirty years after, and Face of the High Arctic (1959) depicts the ecology of the region, produced by the National Film Board of Canada.

Altogether, the films run an impressive 281 minutes. There’s also a booklet with excerpts from Flaherty’s book, My Eskimo Friends, an essay by Lawrence Millman, “Knud Rasmussen and The Wedding of Palo,” and notes on the films.

Snow White and the Seven (?) Bullfighting Dwarves

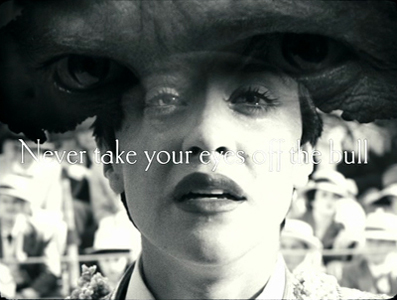

In 2011, a French film, The Artist, gained huge attention in the infotainment media as a modern version of silent cinema, winning yet another Best Picture Oscar for the Weinstein brothers. It was a reasonably successful imitation of mid- to late 1920s cinema during the transition to sound. Now a much better modern silent film has arrived, Pablo Berger’s Blancanieves, a loose version of the Snow White story transposed to 1920s Spain. A famous bullfighter is paralyzed after being gored in the ring. His wife dies in childbirth and his scheming nurse marries him. She keeps his daughter, Carmen, away from her father by setting her to work as a downtrodden servant in his country estate. Upon her father’s death, the evil wife schemes to have her killed, and she escapes to the protection of a troupe of six bullfighting dwarves who, possessing uncertain arithmetic skills, bill themselves as seven bullfighting dwarves.

While The Artist was a fairly good imitation of 1920s Hollywood filmmaking, Blancanieves is a pastiche of the 1928-29 era of European silent cinema. It draws on what I have termed the International Style of filmmaking, a late 1920s blend of influences from the French Impressionism, German Expressionism, and Soviet Montage movements. One could almost pass it off as a genuine film of the era.

At times there are subjective effects à la Impressionism. A superimposition conveys Carmen’s memories of her father’s crucial instructions to her, and superimposed images of hands waving handkerchiefs present the enthusiam of the crowd’s plea for the bull to be pardoned.

This was also the period in which the power of the wide angle lens, particularly in close-ups and in low-angle shots, was exploited, initially in Soviet cinema and then all over Europe. Blancanieves is full of such shots, as in the frame at the top of this entry and in these two shots from the opening scene:

There are also montage sequences, building up to flurries of very short shots. This accelerated-editing technique is typical of both Soviet and French filmmaking of the era.

The too-frequent use of handheld camera in Blancanieves detracts somewhat from the feeling of authenticity. In the late 1920s, cameras were too heavy to be handheld. They could be strapped to the body of the cinematographer with harnesses, but that creates a subtly different look. And during the late 1920s, shots with the camera holding on a character while the background spins around behind him or her would have been achieved by placing both camera and actor on a large turntable. (This effect apparently was pioneered in Germany in the mid-1920s). But the occasional dramatic lighting effects, particularly in the climactic scene, are distinctly reminiscent of German cinema.

In general, the narrative is charming and amusing. The heroine’s pet rooster provides exactly the sort of comic relief that is common in films of the 1920s, and the story has an effective fairy-tale quality. I found the ending a bit disappointing and certainly not typical of the films of the 1920s. Still, Berger has clearly watched an enormous number of 1920s European films and absorbed their styles. He can imitate the International Style remarkably well, telling a tale that is appropriate to the 1920s and yet has a touch of humor that doesn’t belittle the silent era.

Blancanieves was released in the US on March 29 and is currently making the rounds of art-houses and festivals.

Other entries discussing the International Style and wide-angle filming at the end of the silent era can be found here and here.

The Wedding of Palo